|

|

|

|

|

|

1938 Passport Photo Mosze Szymon Rozenbaum

Went to Australia, 1939 |

|

| |

|

My father was born in Radzilow, Poland in 1921 and was the youngest son of Zundel

(Chanoch) Rozenbaum and Rochla Gitla (Alte)

(nee Sawicki). He had 3 sisters, Brajna (Briony), Chajche (Irene) and Shaine, and a brother Yankel, and was the sole survivor of his

immediate family. His father Zundel died 4 weeks before he departed for Australia,

and the

remaining family all perished during the Holocaust. Zundel was the second oldest of 11

children and Alte was one of 3 children (she had a brother Yankel and a

sister Frejda, who left Poland with

her 3 children in 1934 and settled in the US). In Zundel's

family Meir was the oldest, followed by Zundel, Sochie, Fejga, Yankel, Esther,

Moshe, Rochel, Nathan, Chaim and Chajche Rywka.

The family was very religious; Zundel

was a Yeshiva student and attended a Rabbinical College until he married. He

then worked as a scribe, writing letters for people (many of whom were

illiterate) and he had a wonderful style of writing and a way with words. He also

taught a few young and middle-aged students and spent the rest of his time in

religious studies and at the synagogue. He was in very poor health and my father

would always pick him up from synagogue, as he had a weak heart and found it

difficult to walk unassisted. As a result, Alte became the breadwinner, with the help

of her children and family from abroad. Before the Jewish holidays, money came

from relatives in the UK, US and Australia, and Sochie in London also sent parcels

of old clothes, which were then recycled and worn by the family. My grandfather's

most urgent wish was to marry his daughters off, but with no means of getting a

dowry together, this was impossible. The marriage between my grandparents was

an arranged match; Yitzchak Sawicki wanted a Rabbi's son as a son-in-law.

Yitzchak was a wealthy grain merchant and supported them financially. However, in

1919 after WWI, an Act was passed by the Polish Parliament annulling all monies

owed to merchants or landlords, and my maternal gr-grandfather became impoverished

over night. This is when Alte became the breadwinner and survived by selling all

the valuables she possessed, including a pair of gold candlesticks. My father

described her as a beautiful woman with an olive complexion and long black curly

hair.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Police Station, where Mosze Szymon and family lived in

rented premises upstairs |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Front row, middle]:

Yankel Rozenbaum

Yankel killed in

Radzilow, 1941 |

[L-R]: Brajna and

Shaine Rozenbaum

Both killed in

Radzilow, 1941 |

|

|

| |

|

Dad's oldest sister Brajna was 8 years

older than Dad and was a tall, thin, good-looking girl. She helped with the

housework and kept the house spotlessly clean. At one time she was introduced to

an elderly widower from a nearby town. He came several times but nothing

eventuated from the meeting. His second oldest sister was called Irene and she

worked for some relatives on the Sawicki side as a ladies and gents shirt-maker.

She saved enough money to buy a Singer sewing machine and started to work on her

own at home. She had many customers and established a good little business. She

traveled to Warsaw with Dad and bought and paid for all his clothes. His

youngest sister Shaine was 2 years older than Dad and finished primary school.

She was a very good student and always helped Dad with his homework. She helped

her mother with the housework and also helped her sister making shirts. When Dad

left for Australia, she was the one to write on behalf of the family; in her

last letter she told Dad how much the family missed him. Dad wrote back telling

his family how heart broken he was without them. This was the last

correspondence between them. His brother Yankel attended a Yeshiva and was very

well-educated but had to leave to support the family. He became the main

provider selling grain and animal skins. There was a real bond between Dad and

his brother and of all his family, Dad thought that Yankel's dynamic personality

and determination might help him to survive the Poles and the Germans.

As the youngest child my father spent a

great deal of time with his father and absolutely adored him. My grandfather

had many volumes of leather bound Talmudic and religious texts and Dad always

regretted not taking some with him. The only thing my father brought with him

from his parents was a pair of tefilin.

He did not even have a photo of his

mother and father. Zundel would often sit with Dad and talk with him about

religion and the world in general. Dad slept with his father so he could watch

over him and would get up several times a night to see if he was still

breathing. Zundel was a quiet, reserved man, and highly respected by the Jews in

Radzilow. He was a devoted husband and loving father and each Chanukah would

somehow find the money for Chanukah gelt for all his children. The family was

very poor and would often not have enough food to eat. On many occasions Dad

went to school without any breakfast and found it very hard to concentrate on

his studies. He often told us about the times he was so hungry that he couldn't

sleep and would go outside and get a handful of snow to appease his hunger. He

did not have a decent pair of shoes or clothing. They lived upstairs in an old

building in the main street of Radzilow (the police station was downstairs), the

house consisting of 2 rooms and a kitchen, and was always cold and damp, as they

could not afford to buy wood or coal.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Best friends throughout their days in Radzilow:

Arczy (Archie) Fajkowski and Mosze Szymon

Arczy killed in Radzilow, 1941

Mosze went to Australia, 1939 |

|

| |

|

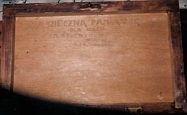

My father was a keen student and

completed 7 grades of elementary school. He always came out on top in math, history,

geography and essay writing. He writes about his best friend Arczy (Archie) Fajkowski

and how they studied together by candlelight, and how Archie would often bring

him a slice of bread and other food to share with him. I still have one of

the notebooks they shared, which contains their school

notes. Before he left Poland for Australia, Archie gave my father a gift of a

wooden box engraved with his initials on it. I still have this box. It was not

possible for my father to further his education after

7th grade due to lack

of money to pay the fees and the difficulty for Jews to continue in higher

education. He then joined a free Jewish discussion group, which was held in the

evenings. At this time he was 15 years old and determined to further his general

and Jewish knowledge.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Wooden Box

Inscription reads: Na Wieczna

Pamiatke, Dla Kolegi,

M. Rozenbauma, Ofiaruje,

A. Fajkowski.

Translation: In token of friendship,

[Literally "For eternal memory"

a common Polish expression when inscribing something like a picture

or a nice present], To my friend

M. Rozenbaum, From A. Fajkowski. |

|

|

| |

|

Radzilow was situated on the East

Prussian Polish Border and with the rise of Hitler in 1933, anti-Semitism became

rife in the area. Jews

were impoverished and forced to beg for food. At times there was no food in my

father's house and my grandmother was forced to sell anything of value to

buy food for her husband and her children. All Jewish shops were picketed and,

if by chance a Pole bought from a Jewish premises, the pickets would pour

kerosene over the goods and burn them. The police did not intervene and looked

the other way. The Polish Government then passed a special law regarding Jews:

the Poles could boycott their businesses but they could not hurt or hit a Jew.

In this way they aimed to starve the Jewish population, most of who were

involved in commerce and trade, and make it impossible for them to exist.

In Lomza there was a Catholic priest

by the name of Trzeciak who was an outspoken anti-Semite, whose main aim was the

destruction of all Jews. He was also a Member of Parliament and the editor of

"Gazeta Polska," a newspaper that consisted entirely of anti-Jewish propaganda and hatred.

It was almost impossible for Jewish students to

obtain higher education. Jewish students at university were not allowed to sit

on the same benches as Poles, and had to stand through lectures and were often beaten up

and badly hurt. There was no one to protect the Jews, and with the Poles demanding

their annihilation, only one voice existed: "Jews to Palestine."

From 1933 onwards the pogroms began,

the worst of which occurred in the smaller towns. In the winter of 1933 a pogrom

took place in Radzilow on market day. In Radzilow, the market used to be held

every Thursday. Jewish small merchants from the district townships used to come

with their merchandise, such as sheepskin coats, shoes, boots, barrels with

smoked herrings, and many other items. The Polish farmers used to bring

different grains, such as wheat, corn, barley and oats. The small Jewish

merchants, mainly from Szczuczyn, used to buy up all the grain, most of which

was sold onto Nazi Germany [Szczuczyn was even closer than Radzilow to the

German border]. The price of grain used to rise daily because Germany was

preparing for war. The peasants

from nearby villages invaded Radzilow, armed with iron bars and lumps of wood, and

attacked the Jews. On the same day the priest

Trzeciak from Lomza came to

Radzilow and delivered a chilling anti-Semitic speech advocating the killing of

all Jews. As soon as he finished speaking, the peasants began robbing all the

Jewish stalls and shops. The Poles killed a Jewish woman [who was in town for

market day, from Jedwabne] and robbed every Jewish home. The police could not control the riots and called for

reinforcements from nearby townships. In order to control the crowd the police

sergeant ordered his police to shoot in the air and 4 Poles were killed; only then

did the crowd disperse. Radzilow was devastated and ruined. My father was at

school and ran home along the fields fearing for his family and was absolutely

petrified by the events. On the Friday, the funeral for the Poles took place,

with the local priest delivering the eulogy. He described the dead as great

Poles and said "that if Jewish blood was not scattered to the four corners of the world,

then Christianity was not meant to survive." The Jews of Radzilow hid in their

attics, too afraid to venture out. This lasted for several weeks. Gradually,

people left their homes to buy food, which was supplemented by basic supplies

from relief agencies. The general situation was frightening and bleak; there was

no future and nowhere to go. Anyone with means left Poland - every Saturday

several Jewish families left for overseas, with quite a few going to Palestine.

It was a constant exodus, with fewer and fewer families remaining.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Late 1930's

Mosze Szymon

working on a

sewing machine

Note: The actual size of the original photo is less than an inch on each side |

|

|

| |

|

My father was really troubled by the

situation and got all the addresses from his father of relatives overseas and

began writing to them, begging them to provide him with the necessary documents

to leave Poland. My father was 13 years old at the time. The anti-Semitism

increased daily and my father and his friends were regularly beaten up by the

Polish boys. One summer while swimming in the river, my father was severely

beaten and had 10 deep welt marks on his back that were unbearably painful.

After this episode, he and his friends did not go swimming again. Even though my

father knew the Polish boys, nothing could be done, as there was one set of laws

for them and none for the Jews. At the same time a young cousin, David Sawicki,

aged 11, was locked in a stable and beaten so badly by the Poles that he passed

away 2 weeks later. It was the first time that my father saw parents burying a

son.

Pogroms continued in town after town

and new anti-Jewish laws were introduced daily. Hitler was preparing for war and

the first words of all his speeches began with "the filthy, dirty, bloody

Jews." It was terrifying to hear this all the time and my father decided to

smuggle himself across the German border at night and make his way to Lithuania.

However, the borders were so heavily guarded that he decided against it. He

received no replies to his pleas for help and felt that the odds to leave were

against him. In 1936 an Act was passed in the Polish Parliament by a Madame Pristerowa to ban the ritual kosher killing of meat. Jewish families were

allowed only 1/2 kilo of meat per week. As the situation deteriorated, Dad wrote

again to family in Australia and within 2 months (August 1936) came a reply from

Ben Rosenbaum (son of Nechemiah and Fejga) saying that he would organize the permit for Dad to come to

Australia. He also paid the fare to Australia of 50 Pounds, which Dad later repaid

after he began working.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Warsaw, 1938

[Back, L-R]: Chajche (Irene), Mosze Szymon, cousin

[Front, L-R]: cousin,

Aunt Rochel, cousin

Mosze went to Australia, 1939

Chajche killed in Radzilow, 1941

Rochel, her husband Yudel, and

3 daughters all killed in Warsaw |

|

| |

|

My Father was overjoyed but had many

sleepless nights thinking about the family he would have to leave behind. He

waited for the post [mail] to come every day with his permit, and as the months went by,

he began to give up hope. Being the youngest in the family, Dad helped his mother

with the household chores and would walk 4 kilometers to a small village called

Dziewiecin to buy 25 kg of corn flour with which to bake bread. The money for

the flour came from overseas relatives and meant that at least the family had

bread for a few weeks. Dad also went to the well to get water everyday, as the

water was not connected to the houses. This was not so difficult in the summer but

was quite dangerous in the winter when everything was covered in ice and snow.

The toilet was outside and the sewerage also had to be taken to the rubbish tip

on a daily basis. Dad also sold grain for a short period to try and bring some

money home, but this only lasted from July to September. In the meantime, Dad

kept writing to Australia and they assured him that the permit was being

processed and that they would pay his fares. At this time, Dad learned that his

cousin Lazar Kajman and family were going to Australia and that they would

arrive there before him. Finally, in July 1938, the permit arrived and my father

and his family were overjoyed. The necessary documents had to be obtained from

Grajewo, and for the first time in his life, Dad went to Warsaw to get his

passport. He traveled by train and on his arrival at the station asked a droshke

driver [horse-drawn carriage] to take him to Franciszkanska 4, the

home of his aunt Rochel (his father's sister). He was in awe of the city. This was his first time away

from home and it was also his first meeting with his aunt and her husband Yudel and their 3 young daughters.

After lunch and in the following

days, his aunt took him to all the necessary offices to obtain his legal

documents. Franciszkanska Street was mainly a Jewish area,

full of Jewish traders selling all manner of goods, and he awoke to the sound

each morning of vendors selling bagels, pastries etc. Dad stayed with his family

for several days and makes mention that this was the first time he had ever seen

an indoor toilet, and that it took him sometime to figure out how to use it. With

all the formalities complete, his aunt and family took him to the station for the

journey back to Radzilow. His passport and visa were to arrive shortly after his

return and all that had to be done was to arrange the date when he was to leave. Everyone

told him how fortunate he was to be leaving Poland, but Dad was brokenhearted to

be leaving his mother, brother and sisters behind. His father died 4 weeks before Dad's

departure. On a Sunday at 4 p.m. on the 2nd day of Shevat in 1939, my grandfather

died in my father's arms. In those days the preparation for burials took place

at home, Dad went to get the men from the Chevra Kadisha, who came and lifted the

body from the bed, laid it on the floor and then covered the body with a

linen sheet. Candles were burning on either side of the body. The funeral took

place on Monday. The body was taken to the synagogue where Rabbi Zelik Gelgor,

the village elders, his brother Yankel, and his family and friends, all paid their

last respects and tributes. The body was then taken to the cemetery where my

grandfather was laid to his eternal rest. There were no coffins in those days and the

body was placed in the grave, and then a 1/2 a meter above the body, wooden boards were

placed along the grave. My father's brother Yankel put the first 3 shovels of

earth in the grave, then it was Dad's turn, and then his uncle Yankel's turn, and

then the grave was filled by relatives on his mother's side of the family. Dad

and his brother recited Kaddish and then returned home without their "jewel in

the crown." The family was devastated by the loss and Dad felt really guilty

about leaving his grieving family. He had not expected his father's death and

always thought he would be able to say goodbye to him.

|

|

|

|

|

|

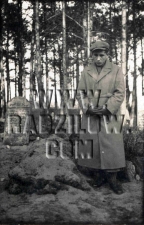

Late February 1939

Mosze Szymon, shortly before leaving Radzilow, paying his last

respects at the fresh grave of his father, Zundel Rozenbaum, who

had passed away only four weeks earlier, on

Jan 22, 1939

Note: This is the only

photo ever uncovered of

the Radzilow Cemetery,

which no longer exists. |

|

|

| |

|

After the Shiva period, Dad had to go to

Grajewo to finalize his emigration papers and to organize the departure date

after the Shloshim Period [shloshim is the Hebrew word meaning 30; in this case

it refers to the first 30 days of mourning]. The week before Dad left, he went to the cemetery with

his best friend Arczy Fajkowski to say his final farewells. Arczy took the photo

of Dad standing at the graveside. A night before the departure, all the family

and his friends came to say goodbye. The most heartbreaking thing of all was saying

goodbye to his mother, brother and sisters. The only consolation was the

possibility of being able to help his family when he arrived in Australia.

Unfortunately this never eventuated and Dad was never to see any of his

immediate family again. Dad's sister Irene went to Warsaw with him and

she and his aunt Rochel went shopping with him and bought a couple of shirts, a

scarf, a gabardine raincoat, 2 pairs of socks and a pair of shoes. His aunt Chajche Rywka, from the nearby town of Garwolin,

especially made the effort to come

and say goodbye. This was the first and last time Dad ever saw this aunt.

|

|

|

|

|

|

February 1939

Mosze Szymon saying farewell

to his friend Wasersztejn, who later went to Israel |

|

| |

|

Towards the end of February, Dad bid

farewell to his sister, aunts and family, and took the train from Warsaw to

the port city of Gdynia [in the Gulf of Gdansk]. He arrived early in the morning; the city was covered

in snow. This was his first sight of the Baltic Ocean. He boarded the small

Polish boat of 3000 tons named The Baltrower about 11a.m. on

a Friday, together with about 40 Jewish people. Several of the passengers ended

up in Australia, where they remained in touch. There was a Rabbi among the

passengers who was given special consent to board the boat on the Sabbath. As

the boat sailed towards Danzig, Dad saw swastika flags on all the buildings and

could feel imminent danger, but not to the extent of the Holocaust that took

place. The journey took 5 days, the sea was very stormy, Dad was very seasick

and was thrilled when they berthed in London.

He arrived in London at the beginning

of March 1939, where his aunt Sochie warmly greeted him. He was kissed and hugged

by his aunt, who wanted to know all about the family (Dad did not tell her about

his father's death) and then taken to 121 Christian Street, off Commercial Road,

East London, to meet the rest of the family. Their business of tailor trimmings

was situated at the front of the building and the family lived at the back. This

business still exists today. Dad spent 11 wonderful days in London meeting his

family and their friends. He helped his aunt make up a parcel of clothing to

send back to the family in Poland. His uncle took him to the synagogue to say Kaddish

for his father and bought a daily Jewish paper with a Yiddish edition so Dad was

able to keep abreast of what was happening in Europe. During his stay, the French

President paid a State visit to London to discuss the deteriorating situation.

Wherever Dad went, people were digging air raid shelters behind their houses

and in all the public parks, in preparation for what lay ahead.

After 11 wonderful days Dad left London. His cousin Nat Kissin gave

him 10 shillings, and this was the only money Dad had for the journey to

Australia. He sailed from England on the March 12, 1939, on the 15,000-ton S.S.

Ormonde, which was luxurious in comparison to The Baltrower. The journey took 6

weeks, during which time Passover was celebrated. Every Jewish passenger was

given a packet of matzoh and a bottle of wine. The first Seder was conducted by

an elderly man named Korczik from Lomza, helped by the chief steward Alec

Goldman, who turned out to be a good friend of Dad's cousin Ben Rosenbaum. The

first port of call in Australia was Fremantle, WA, on ANZAC Day, April 25, 1939.

My father saw his first military parade on Australian soil. This holiday

commemorates Australian and New Zealand soldiers who were killed defending their

countries. The Ormonde arrived in Melbourne on May 1, 1939, and my father was

met by Ben Rosenbaum and Lazar Kajman. Lazar had come to Australia with his wife

Zelda and 2 young sons, Norman and Morry; his father Velvel was Dad's

grandmother's brother on his father's side of the family.

During the boat trip my Father was

terribly homesick and worried about what he would do in Australia with no

friends, no language and no trade. Luckily, his cousin Ben spoke Yiddish and

accorded him a very warm welcome. Dad spent his first weeks in Melbourne at the

home of Ben and Bella Rosenbaum and their young son Maurice, at 4 Ellsmere Road,

Windsor. They had a very comfortable home with a front and back garden and this

was a real eye opener to Dad after the abject poverty of his home in Radzilow.

One evening they took him to the Capitol Theatre and this was the first talking

movie Dad ever saw. They also took him sight seeing around Melbourne and his

impressions were of a very green, clean and beautiful city. He was introduced to

the delights of Devonshire Tea (scones, strawberry jam, cream and a pot of

English tea) and kept thinking how his family at home would enjoy this treat and

the wonderful lifestyle of Australia.

After two weeks with his cousin, Dad

moved to North Carlton (the suburb where all Jewish immigrants lived when they

first arrived in Melbourne), to the home of the Landy's at 557 Nicholson Street,

and shared a room with their son Joe. Ben had to help Dad pay for the room and

board, as he had no money and no job. The only place Dad did frequent was the

Kadimah (a cultural center), which was a meeting place for Jewish immigrants. All

the immigrants were in the same boat and used to exchange stories about looking

for work and about life in general. My father was reserved and shy by nature, and kept

fretting and worrying for his family and friends. He also worried about the fact

that he had no money, no trade and could not speak English, and often thought he

had made the wrong decision in coming to Australia.

The next week his cousin Ben came to

help him look for a job in the clothing trade. He bought him a pair of scissors

for 25 Shillings and Dad's only thoughts were of how was he going to repay his

cousin Ben. He got a job for a week as an under-presser and earned 7 shillings and sixpence. This lasted a week and then

Dad was given the sack. After numerous attempts, he finally got a job but it did

not pay enough to make ends meet and Ben had to supplement Dad's income. He

lasted there for 3 months and then moved to a factory making very cheap staff

shirts, pajamas and trousers. The workforce consisted mainly of women who were

on piecework and worked a 48-hour week, but earned good money for their efforts.

Dad thought to himself that if they can do it so can he, and eventually became the

fastest machinist, making 65 pairs of trousers a day and earning 5 Pounds. With

the first 5 Pounds that he saved, Dad opened a bank account. This was the first

time in his life that he had money of his own.

The price he paid, however, was that he

had to work on Saturdays, and this meant he could not go to synagogue. However, he

went every evening for 11 months to say Kaddish for his father and also whenever he

could with Mr. Landy, but felt guilty about betraying his beliefs. Eventually

Dad was able to attend synagogue regularly, and in later years, was elected 3

times as president of East Melbourne Hebrew Congregation and attended weekly shiurs

[study sessions of religious text]. He also learned English 3 times a week at the Kadimah and managed to

pick up the language quite easily. My father managed to repay his cousin Ben for

the fare to Australia, the scissors and rent money and then saved 10 Pounds (250

zlotys) to send to his family in Radzilow. However, this did not transpire

since war broke out on September 1, 1939. Dad was at his cousin's house on a Sunday evening and

remembers on the way home a Special Edition of The Herald that came out declaring that

England was at war with Germany. Dad was devastated by the news and what would

happen to his family. He received 1 or 2 letters from his brother Yankel, who

told him that all the Polish officers threw away their uniforms after 3 or 4

days on the front line, only the non commissioned officers remained to the end.

Poland was utterly devastated - and after that there was complete silence. Every

evening a bulletin was posted in the Kadimah giving details of missing family

and friends, but Dad never got any news of what happened to his family.

On the Queen's Birthday Weekend, June

1939, Dad had been taken to Shepparton to meet the Rosenbaum family. Fejga and

Nechemiah (Ben's parents) were elderly and Nechemiah suffered from dementia. Dad

also met his uncle Rabbi Goldberg for the first time on Australian soil. His

uncle told him that he had received a letter from Zundel asking him to keep an

eye on Dad and make sure that he goes in the right direction. Dad would also

sometimes visit his father's brother Morry Rose on Sundays, but never felt very

comfortable there as they were not on talking terms with the Rosenbaum's. They

had 2 children Norman and Irene. Norman became a doctor and married out (there

was some talk of him being involved in missionary work), and the last time Dad saw

them was at their father's funeral. He would also visit Ben and Bella on Sundays

and stay to tea. Dad developed a very special bond and friendship with their son

Maurice and that lasted till my father's death.

My father met my mother Tola Liwerant

in the Easter holidays of 1939 and they immediately liked each other. My mother

had arrived from Siedlic on the March 20, 1939,

traveling with an aunt and

family. My mother was also the sole survivor of her family and left behind her

parents and 4 brothers. My parents were engaged in June 1942 and married on

November 26, 1942. They had 2 children: Helen born in 1945 and Arnold born in

1946. Soon after meeting my mother, Dad was called up for military service and

spent 4 years with The 6th Employment Company, which was made up of friendly

aliens (about 150 were Jewish). In Tocumwal, he helped load and unload goods from

trains that had to change gauges and he also stacked ammunition boxes. He worked

very hard in the army and was offered 2 stripes, but declined. In 1944 he was

discharged from the army to work on the orchard at Shepparton and stayed there

for several months before coming back to his wife and baby daughter Helen.

My father then continued to work in the

clothing industry and established his own business, Oban Clothing Company, with 2

partners. This partnership was dissolved in 1958 and my father went on to run a

very successful clothing company. He was extremely well-liked in business and

had an excellent reputation. He was very involved in the Jewish community

and the synagogue and took a keen interest in world politics, and Israel in

particular. In later years he attended classes at the university, went to a weekly shiur, and read widely. He was lucky enough to travel to the UK and the US to

meet his cousins, and kept in close touch with them throughout his life.

My mother died in 1974, aged 55, and my

father later remarried in the mid-1980's. My father became ill in 1999 and died

on December 17, 2001, leaving behind his second wife Miriam, children Helen

and Arnold, and grandchildren Michael and Candy, Elise and Alon.

I was indeed privileged and blessed to

have the most wonderful father and friend any daughter could ever wish for and

will always remember him with deep love and respect. My father valued education

very highly and worked hard to give his children and grandchildren the

educational opportunities that were denied to him. This, together with his love

for his family, was the greatest gift he bestowed on us. I will always be

grateful to my father for writing his story, as it has given me an insight into

his life and that of the family I never knew.

|