|

|

|

|

The Gutsztejn-Zimnowicz family

owned a fabrics store on the north side of Town Square. Yisrael Mejer

was a learned and respected elder in the community. When he passed

away in 1927, his wife Pesza continued to operate the business, along

with the help of her daughters, until she was killed on July 7, 1941,

at the age of 71. The store was well-known throughout the region.

Every Radzilover who left in the 1930's, of an age old enough to

remember things, remembers Pesza and the store. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| References From the Moshe Atlasowicz Memoirs (Covering the Period Around 1910 in Radzilow): |

|

From Chapter 12: A few days after I returned home, Father

took us to the tailor and then to the fabric store of Reb Yisrael Mejer

[Gutsztejn] which was wholly managed by his energetic and capable wife [Pesza (nee Zimnowicz)

Gutsztejn]. On that visit to the store, an incident occurred that implanted itself on my mind.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reb Yisrael Mejer and his wife,

Pesza (nee Zimnowicz)

Gutsztejn

Yisrael Mejer died in Lomza, 1927

Pesza killed in Radzilow, 1941, at age 71 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gutsztejn-Zimnowicz house and fabrics store, located on Lomzynska Street,

on the northern side of Town Square |

|

|

| |

|

|

1926 |

|

|

1930 |

|

|

Business Directory Listings

Israel Gutsztejn (Textile Merchant)

He had died in 1927, but the shop

continued to be listed under his name |

|

|

| |

|

After looking over several bolts of

cloth, Father found one to his liking. He asked the price, and Peshe, Reb Yisrael

Mejer's wife, said "$1.90" (meaning per yard). Father, however, knew

how to bargain with her. In the past, with several boys in the family, we had

been good customers, and Father said, "Come now, $1.50 would be too

high."

The woman began swearing that her own

cost was above that. "Reb Joseph, you should live long, it's costing me more than $1.50, I should live so!

May God grant me and my husband the joy and happiness of leading our daughters

to the altar and reverse this, my most cherished hope, if I am not telling the

truth."

Her husband was standing in the doorway,

and he spoke up. "Peshe," said he, "If you wish to swear by

yourself, that is your privilege. The same about our children, they are yours.

But please, leave me out!"

As in the past, Father purchased the

material at a price allegedly her own cost. I was confused and on the way home I

gathered up enough courage to ask Father how she, a pious woman and wife, would

first swear as to her own cost and then sell the material at her supposed cost.

"How," I asked him, "can she stay in business selling merchandise

below her costs?" Father smiled and said "Keep this to yourself, but

Yisrael Mejer explained it to me once. It's really quite simple. You see, she

figures that the minimum profit that would enable her to exist is thirty per

cent. Accordingly, she adds thirty percent to the actual cost and the total, she

figures, is her gross cost. Anything above that is profit."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Moshe Gutsztejn,

early 1920's

Left Radzilow, mid-1920's, went to Kovno, Lithuania, then to Cuba |

|

From Chapter 9: Most of the Jewish community was very

critical of my attending school, and some didn't hesitate to express their views

to Father, in unreserved language. One of them, Reb Yisrael Mejer, was more

outspoken than anyone else. He was a frequent visitor to our house because of

the two daily newspapers "Der Itoment" in Yiddish and the "Hazfirah"

in Hebrew, which Father subscribed to. Reb Yisrael Mejer was too miserly to

subscribe to a newspaper himself. Leaving his business, a retail fabric store,

to his wife and daughter to manage, his wife was recognized as a better business

manager than he, he would often come to our house to read Father's newspapers.

He was in the habit of bringing up the

subject of my schooling, even in my presence, showing open hostility. He often

warned Father if he didn't stop my schooling, I would unquestionably wind up a

Mumer Leachis (one who spites God), or perhaps even a Meshumad (a willing

convert from Judaism; an apostate).

Father was clearly provoked and always

annoyed. On one such occasion, he told Reb Yisrael Mejer he was a shoteh (one who

lacks sense). Finally, when that failed to have its effect and Reb Yisrael Mejer

continued with his angry criticism, Father said to him, "Listen, have I

ever intervened in your plans for the education of your own Moshe? Why, in the

name of heaven, don't you leave the upbringing of my son to me?"

On another occasion, Father said to him,

"I am not God's bodyguard. If Moshe should disobey His laws, or act

contrary to His will, He will deal with him in His own way."

|

|

|

[Editor's Note]: My grandfather Moshe

Gutsztejn was about 3 years older than Moshe Atlasowicz, and therefore not

among the same group of friends, or in the same grade at school. The

reference takes on context because both men had a son named Moshe. |

|

|

|

| From Chapter 33: On one occasion, I stepped out of the house and walked over

to the barn, to visit the "Aristocratic lady." I had taken a liking to the cow,

and often went over to feed her hay. Inadvertently (I never did it intentionally), I was

without a cap. As I reentered the house, there were two men with Father in the

drawing-room. One of them was Reb Yisrael Mejer who, for years past, had been coming to our

house to read Father's newspapers. He immediately noticed my bare head and stared at

me. The moome motioned to me to come into the next room where she asked me to put on my

cap. Returning to the drawing room, I found Father and his two visitors absorbed in a

discussion about news of an earthquake. From the discussion, I concluded that the loss of

property and human life was extensive. Suddenly, Reb Yisrael Mejer turned to me and said,

"Moshe, Tanna Rabah (great sage), perhaps you can explain to us what causes such

catastrophes as earthquakes and volcanoes?" I went to my private "library"

and withdrew two text books, one on geography and one on physics and proceeded to explain

as well as I could, showing them a number of illustrations supporting my explanations. All

three men listened intently, but Reb Yisrael Mejer said, "According to your books and

your explanation, it's all caused by natural forces, eh? It has nothing to do with

God's will?; He has no control over it, eh?" I was stunned at his reaction, as I

feared that Father might share his fanatical sentiments. To my deep amazement, Father came

to my rescue. He removed a volume from his large bookcase, turned a number of pages and,

finding the spot he was searching, began to read aloud. It was in Hebrew, and it dealt

with the science of astronomy. The portion Father was reading explained how planets

probably were formed, that the earth was only one planet in our own solar system, and that

there were a great many more such suns and planets in the universe. Reb Yisrael

Mejer interrupted him. "Now," he said, as if something had suddenly dawned on him,

"now I understand something I didn't for several years. I had wondered why you

permitted your son to go to school instead of to cheder and the Yeshiva. It is the old

saying: 'the apple falls nearest its own tree, the tree that bore it.'"

Father calmly said to him, "You are a shoteh (stupid person)."

|

|

|

[Editor's Note]: The remarks made at

my gr-grandfather were understandable in the context of the times. My gr-grandfather's

views were entirely typical of other learned Radzilover men mentioned

throughout the memoirs. In fact, they're most of the same views that young

Moshe's father, Joseph Atlasowicz, likewise held. But as the old adage

states, blood is thicker than water, and Joseph always rose to the

occasion to defend his own son against others, when, by and large, he felt

exactly the same way and is quoted as saying similar things in other

chapters. |

|

|

|

| Comments by the Giselle Wildman,

granddaughter of Chaya and Yisrael Finkielsztejn

(who survived the Holocaust in Radzilow):

"It is wonderful to see that your

family lived and worked so close to our family home and mill. Interesting

to note, my grandparents bought a lot of fabric before the war as my

grandmother Chaya ,apparently felt that it would be (and

indeed did become) a very important currency during the war. They had lots

of fabric which they exchanged for things they needed while they were in

hiding. It actually helped keep them alive. They must've bought it from

your family." - Giselle Wildman |

|

|

[Editor's Note]: There's no doubt

Chaya bought the fabric from the Zimnowicz store, as it was the only place

in Radzilow to do so. According to several landsmen who left Radzilow in

the late-1930's, the Zimnowicz store was the place to buy fabrics. |

|

|

|

|

Postscript:

Yisrael Mejer and Pesza had eight

children. Two died as young children in Radzilow. Moshe emigrated to Cuba in

the mid-1920's. Chana emigrated to Israel in 1932. The

other four were killed in the Holocaust, along with their spouses and

children.

After Yisrael Mejer passed away in 1927, his wife Pesza continued to manage

the fabrics store until she was killed on July 7, 1941, at the age of 71.

The three daughters who remained in Radzilow all continued to help out with

the business until 1941.

|

|

|

|

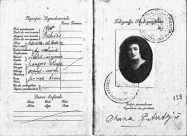

Yisrael and Pesza's daughter Chana |

|

|

|

|

|

Chana Gutsztejn and her

Polish Passport, 1932

Went to Israel, 1932 |

|

|

|

|

|

Yisrael and Pesza's daughter Sara |

|

|

|

|

Sara (nee Gutsztejn)

and Yankiel Zimnowicz

Both killed in Radzilow, 1941,

along with daughter Shulamit, age 8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yisrael and Pesza's grandchildren from

their son Jankiel |

|

|

|

|

|

Children of Jankiel Gutsztejn and wife Yocheved, 1936

[L-R]: Ephraim,

Yitzhak,

Rywka, Yisrael and Menachem

Entire family of seven

killed in Holocaust |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|