|

|

|

|

|

|

Chana Finkelstein (Ann Walters)

as a child in Radzilow, Poland, 1937-38.

She was seven years old at the time

of the massacre in Radzilow in 1941. |

|

| |

|

"We heard the shots, and we saw

that the barn was burning, so we started running," said Kansas Citian Ann

Walters of the pogrom in her hometown of Radzilow, Poland. "We saw the

smoke and heard the screams. It's impossible to describe those moments."

On July 7, 1941, 500 Jews - men, women

and children - of the town of Radzilow were rounded up, locked in a barn, then

burned or shot to death by fellow Poles. By the end of the day, 300 more would

be murdered.

It is for such moments that the terms

Shoah and Holocaust were coined.

Walters, who has been living in

Kansas City since 1957, is now the sole survivor of the Radzilow massacre -

which took the lives of every Jew in Radzilow save eight - Walters's family of

six and Mojzez Dorogoj and his son, Akiwa, who were murdered when they returned

to Radzilow after the war. Before the massacre, Jews had comprised about half

the population of the rural town.

Radzilow is about nine miles north of the

town made infamous in Jan Gross's 2001 book, "Neighbors: The Destruction of the

Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland." What happened in Jedwabne had happened in

Radzilow three days earlier.

Seven-year-old Chana Finkelstein, as Ann

Walters was known then, along with her parents, Israel and Chaya Finkelstein,

and siblings, Menachem, 18, Yaffa, 13, and Sholemki, 9, escaped the carnage in

Radzilow by hiding in a nearby wheat field.

As in Jedwabne, the slaughter was done

entirely by Poles, not Germans, according to the testimony of Menachem

Finkelstein, taken by the Jewish Historical Commission four years after the

event. (The full text can be read in the Holocaust section of the Web site

www.radzilow.com.)

By mid-1941, Hitler had already taken

over much of Poland, but he had not yet deported the majority of its Jews to

concentration camps. But the area had a history of anti-Semitic pogroms, and

they were a renewed threat with the Nazi anschluss.

"At midday, a lot of Poles from the

neighboring town of Wasosz came to Radzilow," wrote Finkelstein. "It was

immediately known that those who came had previously killed in a horrible manner

... not sparing even women or little children. A horrible panic broke out.

People understood that this was a tragic signal of destruction. Immediately all

the Jews, from little children to old men, fled the town for neighboring fields

and forests. No Christian let any Jew into his house or offered any help. Our

family also ran in the fields and when it got dark, we hid in a field of wheat."

"On the day of the burning," recalls his

youngest sister almost 60 years later, "we ran out of Radzilow. We really didn't

trust anyone at the time."

The Finkelsteins' survival was aided by

two things: the father's business contacts from the flour mill he owned and the

family's feigned conversion to Catholicism.

"My parents promised the Poles that if we

all survived, they would get paid," said Walters. And in the meantime her mother

had had the foresight to stock up on fabric - hard to come by during the war -

which was used to help purchase the family's safety.

"My mother was a force to be reckoned

with," said Walters, smiling. "My mother would make a plan, and my father would

execute the plan. They were quite a team."

Even so, the Finkelsteins had to keep

moving, from family to family and place to place, because of the extreme danger

involved in harboring Jews.

'Sweet Childhood'

The Finkelsteins stayed in hiding for

more than 40 months after the burning of the barn. During that time, Walters

said, her mother would often hold her and tell her stories. The Finkelsteins

were ardent Zionists.

"She would tell me the history of the

Jewish people," recalled Walters. "If I would be the only who survived, I should

know who I am and go to a Jewish community and to strive to get to Palestine."

The Jewish population of Radzilow was one

with long roots - the beit midrash had existed for more than 500 years,

according to Chaya's testimony, on file with Yad Vashem, Israel's memorial to

and documentary center of the Holocaust.

Chaya and Israel Finkelstein were among

the founders of a Zionist organization in Radzilow in 1917. In the poor, rural

town, they created a library of 500 books, opened a reading hall with Zionist

newspapers and journals, learned Hebrew and arranged for immigration to Israel.

The next year, when the Poles regained independence - during World War I Russia

fought Austria and Germany, often on Polish territory - the library was

destroyed by the Polish military. Oppression was bad enough that many Jews

emigrated to Israel or to South America.

Radzilow experienced its own in 1933 with

beatings, lootings and not one window in a Jewish home remaining unbroken.

Yet Jewish life went on.

"I had a very sweet childhood," said

Walters. "I was the youngest of four, and they tell me I was cute. Everybody was

pampering me and played with me."

But her playmates were all Jews.

"The Poles didn't like Jewish kids," she

said. The only non-Jews she knew were in public school, where the classes were

mixed. Afternoons she also attended a Hebrew school that her parents had been

instrumental in establishing.

When Hitler broke his pact with Stalin

and invaded the Russian-controlled sector of Poland in 1941, disorder increased

and the situation for Jews worsened, culminating in the massacre of July 7.

"I grew up pretty fast," said Walters,

whose family remained in hiding for nearly four years after the day of the

burning barn and the liquidation of Radzilow's Jews.

"My mother remembers all this in amazing

detail," said Dr. Giselle Wildman, Walters' daughter who lives in Overland Park

with her husband, Dr. John Fasbinder, and her son, Alex Wildman. "She said that

things that happen on her own skin she remembers vividly."

Net of Memory

Anna Bikont, a journalist on the staff of

Gazeta Wyborcza, Poland's most widely circulated newspaper, is writing a book

chronicling what happened in Radzilow. She visited Kansas City last month to

interview the sole survivor.

Bikont didn't find out until she was 30

that her own mother had been born Jewish and had converted to Christianity years

before in order to protect the family. After reading Jan Gross's book,

"Neighbors," Bikont felt personally involved and started researching Radzilow.

|

|

|

|

|

|

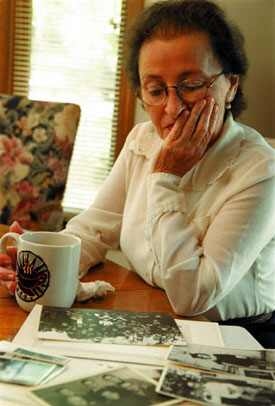

Ann Walters reviews some of her

memorabilia relating to Radzilow.

Photo by Bob Johnson. |

|

|

| |

|

Bikont spent three days with Walters,

poring over photos and reliving memories.

One might say the meeting came about as

the result of the Internet.

In January this year, Dr. Wildman did a

search for Radzilow on the World Wide Web.

"I was thinking, 'Maybe there's some

family out there who survived by chance,' " she said.

"Then I came upon this Web site, and my

jaw dropped. My mother's family's picture was there, and my mother's picture was

there."

The Web site,

www.radzilow.com, was created and is

maintained by Jose Gutstein, a Miami lawyer whose family moved from Radzilow to

Cuba in the 1920s. It features extensive articles, photos and testimonies of the

people of Radzilow, including those of Chaya Finkelstein and Menachem

Finkelstein. Gutstein is also in the process of translating a book by Chaya from

Yiddish into English.

After Wildman contacted him, Gutstein

connected the journalist, who had previously contacted him, with the survivor.

When Bikont left, said Dr. Wildman, her

mother was in tears.

"For the first time someone really,

really listened to her story," she explained. "There are even some people who

say my mother's not a Holocaust survivor because she didn't go to the camps."

Escape From Poland

After the Nazis were defeated, in 1945

the Finkelsteins finally escaped from Poland. Because the British, who then

ruled Palestine, forbade Jews from going to Eretz Yisrael, the family went to

Selvino, Italy. Chana and Sholemki, the youngest two, stayed in a camp for

children. Menachem and Yaffa, then teen-agers, worked with Youth Aliyah Bet - an

underground movement to get Jewish children to Palestine. Parents Chaya and

Israel were able to enter Palestine, in 1946, and began preparing a home in

Rehovot in anticipation of their children being able to make it, as well.

When Chana was 12, she and her brother,

along with hundreds of other illegal immigrants, boarded a boat bound for

Palestine. The craft was intercepted by the British just off the coast. The

children attempted to fight off the British with sticks, stones and bottles, to

no avail.

"They took us to the camps at Cyprus,"

Walters said.

While there, Chana and Sholemki continued

their studies with madrichim, teen-aged teachers travelling with the children

who kept them in order and taught them Jewish history, general studies and

Hebrew.

They wound up in pre-state Israel as the

result of what Walters called "a human touch from the British."

"Kids who had parents in Israel, they

allowed the kids to join their parents in Israel," she said.

Eventually, the older two children joined

them as well, and the family's life approached something close to normalcy -

school, home, father working in a flour mill.

In 1948, Israel's war for independence

broke out. By then Menachem was in Switzerland, studying to be an architect.

Sholemki became a soldier and was killed in a battle during the War of

Independence.

Later, after high school, Chana joined

the Israeli army for two years, rising to the rank of sergeant. Then, a few

years later, she met Kansas Citian Sam Walters, who was in Israel to visit his

brother, Harry. Harry Walters, a Polish-born landsman then living in Israel, was

a business partner of Chana's brother, Menachem. Harry and Anne married and

moved to Kansas City in 1957; a few years ago they divorced.

The descendants of Israel and Chaya

Finkelstein now number 19. One of their great-grandsons, 12-year-old Alex

Wildman - son of Dr. Wildman and grandson of Walters - is a sixth-grader at

Hyman Brand Hebrew Academy.

Dr. Wildman said she was an inquisitive

child and learned her mother's life story as she grew. ("I would never have

burdened her with it," said Walters.)

At the end of the Chronicle interview,

Dr. Wildman turned to her mother and asked, "Do you think it could happen

again?"

Walters was quiet.

"I hate to think," she said at last, "but

I wouldn't rule it out. I wouldn't rule it out. We have to be vigilant," she

added, "and not wait until things start to happen before we recognize what's

happening and what we need to do." |